50 Years After Biafra: Lessons From Aburi Conference

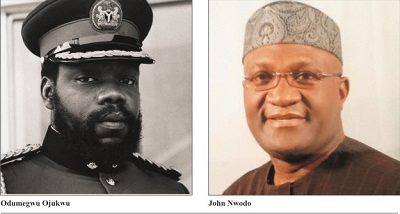

The President General of Ohanaeze Ndigbo, Chief John Nnia Nwodo, delivered a heart-rending speech last week, in Abuja to mark the 50 years of the declaration of Republic of Biafra. His speech recalled the realities of the past yet evoked the realities of the moment.

“Before the war national unity was the norm. A Biafran was a member of Northern Nigeria House of Chiefs.Biafrans lived freely and invested in all parts of Nigeria. In Lagos,Dr Azikiwe was elected leader of Government Business.Mbonu Ojike was elected Deputy Speaker. In Enugu, Alhaji Umoru Altine, a Fulani man was elected Mayor of Enugu.Mr. Willougby, a Yoruba man,was Accountant –General.”Nwodo said.

“Nigeria cannot prosper,as it should,unless we redress some aspects of our current condition”, he added.

What comes to mind quickly with this are the points of discourse and negotiation at the Aburi, Ghana Conference which preceded the Nigeria-Biafra conflict. Issues of fiscal federalism, devolution of power, strong-man as against strong institution,ethnic dominance, coup plots, among others. 50 years after, these maladies are still here with signs of wars to come. What should one learn from the Aburi conference? It is served.

After Nigeria was dragged to the brink of the abyss by two military coups in 1966, its military leaders met to try to bring the country back from the brink. The meeting evolved into perhaps the best documented constitutional debate of all time which touched upon fundamental concepts regarding the balance of power between the central government and federating regions in a federation and professional soldiers’ outlook to military coups and seniority. It was a potential breakthrough occasion.

Following a second bloody army coup in July 1966, the members of Nigeria’s then ruling military junta, the Supreme Military Council (SMC),between January 5th and 7th 1967, met for the first time at Aburi in Ghana under the auspices of the Ghanaian Head of State: Lt-General Joe Ankrah. Ankrah who was no stranger to coup plots as he had become Ghana’s first military Head of State after Ghana’s first President Kwame Nkrumah was deposed in a coup while Nkrumah was abroad visiting China. Ankrah was later forced to resign in April 1969 after admitting his role in a bribery scandal. Ankrah had served in the Congo during the UN peace-keeping mission there in the early 1960s and it is likely he personally knew the Nigerian soldiers (including Ironsi, Fajuyi, Ojukwu and Gowon) who served in the same mission. The meeting at Aburi was the first official meeting of all Military Governor of the eastern region of Nigeria: Lt-Colonel ‘Emeka’ Ojukwu had refused to attend any SMC meeting outside the eastern region of Nigeria due to concerns over his safety. The massacre of tens of thousands of Igbos in northern Nigeria only heightened Ojukwu’s sense of isolation and insecurity. In turn, Ojukwu’s public distrust towards the SMC (whom he suspected of tacitly supporting, or having a hand in the massacres) served to antagonise the SMC, who began to suspect that Ojukwu was planning the secession of the eastern region from the rest of Nigeria.

The fashionable political theory being bandied about in Nigeria today is that a “Sovereign National Conference” (SNC) should be held to resolve the country’s constitutional problems and coup plotting culture. Many do not realise that Nigeria has already had half a dozen constitutional debates – none of which has ever resolved the nagging problems which have dogged Nigeria from independence till today. Nigeria has wasted billions of Naira on constitutional debates and constitutions that are no longer in use, and a future SNC is unlikely to discuss anything that has not already been covered in the previous constitutional debates. Ironically, the best recorded of these constitutional debates was never implemented, and Nigeria has been paying the price since. To plan for the future Nigeria might do well to go back into its archives and learn from the “SNC” which it has already had.

THE ONE AMBITIOUS MAN AND THE REST OF THE COUNTRY QUOTE.

In the months preceding Aburi, the SMC and Ojukwu had engaged in a war of words with the two sides trading multiple accusations and blaming each other for causing or exacerbating the crisis. The Military Governor of the north: Lt-Colonel Hassan Usman Katsina dismissed Ojukwu’s confident and eloquent public statements on the crisis as attempts by Ojukwu “to show how much English he knows or learned at Oxford”. As far as Katsina was concerned, Nigeria’s problem was a stand-off “between one ambitious man and the rest of the country”.

Throughout the six months following the coup of July 29th 1966, Ojukwu repeated his mantra that “I, as the Military Governor of the east cannot meet anywhere in Nigeria where there are northern troops”. That virtually ruled out an SMC meeting inside Nigeria’s borders. Ojukwu had even turned down offers to attend an SMC meeting on board a British (whom Ojukwu, and Igbos in general did not entirely trust) naval ship, and at Benin, but was finally convinced to attend in the neutral territory of Aburi in Ghana. Ojukwu’s aides were not without doubt. Some warned him that the Aburi meeting could be a trap set by anti-Igbo members of the Federal Government to arrest or kill him. Ojukwu brushed aside their concerns by pointing out that he had received a guarantee of safe passage from Lt-Colonel Gowon, and that he had to trust Gowon’s word as an officer and a gentleman. Virtually everything discussed at that Aburi conference is relevant till today. So much so that a reader would be tempted to believe that the discussion was on Nigeria’s current problems, rather than over 40 years earlier, in 1967.

It is probably the best recorded constitutional debate in history. Aware that something momentous was occurring, the Ghanaians had the conference tape recorded. The tape of the discussions was later released by Ojukwu as a series of six long playing gramophone records.

In attendance on the Nigerian Federal Military Government (FMG) side were:

NAME & POSITION

Lt-Colonel Yakubu Gowon, Head of the SMC

Commodore Joseph Akinwale Wey, Head of the Nigerian Navy

Colonel Robert Adeyinka Adebayo Military Governor of the Western Region

Lt-Colonel Hassan Usman Katsina, Military Governor of the Northern Region

Lt-Colonel David Akpode Ejoor, Governor of Mid-west Region

Major Mobolaji Johnson, Military Governor of Lagos

Alhaji Kam Selem, Inspector-General of Police

Timothy Omo-Bare Police

Eastern Delegate:

Col Emeka Ojukwu Governor of South East

(Head of the SMC as Ironsi’s whereabouts were “unknown”)

Ojukwu was in attendance as the Eastern Region’s Military Governor. The FMG delegation arrived “wreathed in smiles” and anxious to mollify their former brother-in-arms Ojukwu. Colonels Adebayo and Gowon even offered to embrace Ojukwu. However Ojukwu was still stung by the terrible massacres of his Igbo kinsmen in northern Nigeria the previous year and was in no mood to embrace his former colleagues. The contrast in the demeanor of the participants was in itself a microcosm of what took place over the course of the next two days. While the federal delegation behaved as if the Aburi conference was a social gathering to reunite former friends who had fallen out in a social tiff, Ojukwu saw the conference for what it really was: a historic constitutional debate that would determine Nigeria’s future social and political structure.

Typically, western world’s perspective was focused on image, rather than on the genuine problems of the protagonists. As secret diplomatic dispatches later declassified by the United States State Department depicted the FMG-Eastern Region stand-off as a personality clash between Ojukwu and Gowon. According to the American perspective: “many Americans admire Ojukwu. We like young, intelligent and romantic leaders, and Ojukwu has panache, quick intelligence and an actor’s voice and eloquent/fluency. The contrast with Gowon – troubled by the enormity of his task, not ass educated, painfully earnest and slow to react, hesitant and repetitive in speech – led some Americans to view the Nigerian-Biafran conflict as a personal duel between two mismatched individuals”.

As they were busy fighting in Vietnam and fighting a “cold war” against the USSR, the Americans did not become militarily or politically involved in the dispute. Instead, treating the conflict as one falling within Britain’s sphere of influence.

THE REUNION OF FORMER COLLEAGUES

The Ghanaian host, Lt-General Ankrah made a few introductory remarks and reminded his guests that “the whole world is looking up to you as military men and of there is any failure to reunify or even bring perfect understanding to Nigeria as a whole, you will find that the blame will rest with us through the centuries”.

Ankrah added that although he understood that the Eastern Region/rest of Nigeria stand-off was an internal matter for Nigerians, they should not hesitate to ask him for any help should they feel the need. Although Commodore Wey played an avuncular role, the discussion revolved around the younger Colonels: Adebayo, Ejoor, Katsina, Ojukwu. and Gowon.

Ojukwu showed from the beginning that he was prepared for serious business. He arrived at the conference armed with detailed notes, and army of secretaries. The extent of Ojukwu’s pre-preparation is shown by the fact that he gave the other debaters copies of documents he had prepared in advance, which enunciated his ideas. The other debaters should have realised at this point, that something serious was going to occur. After the hostility and bitterness that preceded the Aburi meeting, the civilian observers were stunned at the camaraderie displayed by the military officers. The debaters threw off formality and addressed each other by their first names: “Emeka”, “Bolaji”, “Jack” (nickname of Lt-Colonel Gowon) were thrown around as if addressing each other in at a social gathering. One of Ojukwu’s secretaries was amazed to observe that “the meeting went on in a most friendly and cordial atmosphere which made us, the non-military advisers, develop a genuine respect and admiration for the military men and their sense of comradeship. The meeting continued so smoothly and ended so successfully…, that I for one, was convinced that among themselves, the military had their own methods”.

Ojukwu decided to show his good faith, and to test the good faith of the others by asking all present to renounce the use of force to settle the crisis. Ojukwu’s motion was accepted without objection. While this request by Ojukwu may sound very noble, he was in fact playing a cunning soldier-politician. Ojukwu (despite his boasts of the eastern region’s military prowess) realised that he could not succeed in a military campaign against the far more heavily armed FMG. By getting them to renounce the use of force, Ojukwu was trying to negate the FMG’s military advantage. For he knew that if the political situation eventually got out of control, the FMG would find it difficult to resort to a military campaign having already given their word that they would not use force. This may have been an influential factor in Gowon’s subsequent reluctance to engage the Eastern Region in a fully fledged war.

POLITICIANS

The assembled military officers struck a chord in unison on the subject of politicians. All of them voiced their contempt for the behaviour of civilian politicians whom they blamed for the wholesale bloodletting of the previous years (ignoring the fact that more Nigerian civilians had been murdered by politically motivated violence, in the one year of military rule so far, than in the preceding five years of civilian democratic rule). Commodore Wey slammed the point home rather forcefully when he declared that “Candidly if there had ever been a time in my life when I thought somebody had hurt me sufficiently for me to wish to kill him it was when one of these fellows [politicians] opened his mouth too wide”.

IRONSI’S FATE

Despite Ironsi’s murder six months earlier, no public announcement regarding his death had been made and his whereabouts were still presumed unknown, although most of the SMC definitely knew he was dead. Gowon’s regime had eerily repeated the mistake made by Ironsi himself: failing to publicly acknowledge the army officers killed in a coup d’etat.

By not announcing Ironsi’s death, Gowon also made his own position tenuous and gave Ojukwu the opportunity to reason that since the Supreme Commander Ironsi was “missing”, only the officer directly behind Ironsi in army seniority could replace him as Supreme Commander. Major Mobolaji Johnson encapsulated the issue that the east was steadfastly refusing to recognize Gowon as Head of State while the other regions accepted him (albeit tentatively in the case of the west): “The main problem now is that as far as the east is concerned, there is no central government. Why? This is what we must find out. …, For all the east knows the former Supreme Commander [Ironsi] is only missing and until such a time that they know his whereabouts they do not know any other Supreme Commander. These are the points that have been brought out by the east.”

Ojukwu demanded that Gowon make a categorical public statement on the fate of Ironsi. Ejoor supported this by flatly requesting “we want to know what happened to Ironsi and Fajuyi”. Despite Ojukwu’s request for an announcement, most, if not all the participants already knew that Ironsi had been murdered. But the surprising fact was the silent of the Yoruba personnels in the meeting , knowing the fact that their brother Fajuyi was also declared missing.

Gowon was informed of the death of Ironsi and Fajuyi not long after they had been killed. Gowon’s ADC Lt William Walbe was one of the junior northern soldiers that led Ironsi and Fajuyi into a bush alongside Iwo road outside Ibadan and murdered them there. Colonel Adebayo had ordered a search for their bodies, which were eventually discovered by the police. The head of the police Kam Selem would have been informed when his men discovered the bodies.

Although Ojukwu was several hundred miles away in the east when Ironsi and Fajuyi were murdered, he likely would have had the story of their death relayed to him by one of Ironsi’s ADCs Captain Andrew Nwankwo who was captured along with Ironsi and Fajuyi but managed to escape moments before they were shot. Nwankwo eventually managed to find his way back to the east.

Commodore Wey acknowledged that all the debaters already knew what happened to Ironsi. Ojukwu simply wanted Gowon to publicly acknowledge what the SMC members already knew: that Ironsi was dead. Ojukwu later acknowledged that “I heard the rumour that he [Ironsi] had been assassinated, so I began making contacts because I wanted to force them out in the open so that we could start dealing with the real situation.”

Gowon agreed to make a public announcement, and Kam Selem concurred, although he counselled that “the statement should be made in Nigeria so that the necessary honour can be given”.

The soldiers agreed to make a public statement formally announcing Ironsi’s death shortly after they returned to Nigeria, and at this point, the microphones were switched off and the civilians were asked to leave the room. Gowon then narrated the grisly tale of how Ironsi and Fajuyi had been abducted from State House in Ibadan by junior northern soldiers (including Gowon’s ADC Lt Walbe) standing right behind them, driven out to an isolated bush outside Ibadan and shot there.

COUP PLOTTERS: OJUKWU’S PROPHECY

When Ojukwu expressed his disgust over the murder of Igbo army officers by their northern colleagues in July 1966, Lt-Colonel Katsina interjected by asking Ojukwu why he had not reacted with the same revulsion when senior northern military officers were murdered by Igbo soldiers seven months earlier. Ojukwu now explained and reasoned that against th falsehood been spread but in January 1966, soldiers from every region of the federation (Nzeogwu: Mid-West, Ifeajuna-East, Ademoyega: West, Kpera: North) had staged a coup in which soldiers and politicians from every region of the federation (Akintola: West, Balewa: North, Unegbe: East, Okotie-Eboh: Mid-West) were also killed.

Whereas when northern soldiers staged a revenge coup in July, soldiers from one region of the federation only (North: Danjuma, Murtala, Martin Adamu etc) singled out soldiers from one region in the federation as their targets. Katsina took this opportunity to remind Ojukwu of the effort he had put in to prevent the murder of Igbos. Katsina told Ojukwu that “If you know how much …we have tried to console the people to stop all these movements and mass killings, you will give me and others a medal tonight.”

Despite agreeing to attend the conference, Ojukwu was still refusing to recognize Lt-Colonel Gowon as Nigeria’s Head of State. Ojukwu had defiantly continued to address Gowon as the “the Chief of Staff (Army)” (the post which Gowon occupied before the July counter-coup) in his public statements. Ojukwu was alarmed at the ascension of Gowon to the highest office in the land despite the presence of several other officers who were more senior than him (Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, Commodore J.E.A. Wey, Colonel Adebayo, Lt-Colonels Hilary Njoku, Phillip Effiong, George Kurubo, Ime Imo, Conrad Nwawo and Lt-Colonels Ejoor and Ojukwu who were promoted to Lt-Colonel in the same week as Gowon).

Ojukwu almost prophetically warned that allowing a middle ranking officer backed by coup plotters to become the Head of State irrespective of seniority would create a dangerous precedent which Nigeria would find difficult to emerge from in future. He told Gowon that “any break at this time from our normal line would write in something into the Nigerian army which is bigger than all of us and that thing is indiscipline, How can you ride above people’s heads purely because you are at the head of a group who have their fingers poised on the trigger? If you do it you remain forever a living example of that indiscipline which we want to get rid of because tomorrow a Corporal will think, he could just take over the company from the Major commanding the company…”.

Ojukwu’s warning was of course not heeded and his prediction that junior officers would in future overthrow their superior officers proved prophetic. The NCOs and Lieutenants that shot Gowon to power graduated into the Colonels that overthrew him exactly nine years later. The remnants of the same offiers, now as Brigadiers, overthrew the elected civilian government of Shehu Shagari on the last day of 1983, and later removed Major-General Buhari from power in 1985.

Ojukwu’s impassioned monologue at Aburi could serve as an anti coup plotter thesis. He continued to Gowon “you announced yourself as Supreme Commander. Now, Supreme Commander by virtue of the fact that you head or that you are acceptable to people who had mutinied against their commander, kidnapped him and taken him away? By virtue of the support of officers and men who had in the dead of night murdered their brother officers, by virtue of the fact that you stood at the head of a group who had turned their brother officers from the eastern region out of the barracks they shared?”.

THE STAR OF THE SHOW

It was obvious to the non military observers of the Aburi conference that Ojukwu “was clearly the star performer. Everyone wanted to please and concede to him”. On the federal side, only the Military Governor of the Northern Region: Lt-Colonel Hassan Usman Katsina, seemed to realize the significance of what was going on. Anxious not to allow Ojukwu’s domination of the proceedings to continue for too long, he at one point dared Ojukwu to “secede, and let the three of us (West, North, Mid-West) join together”.

Alarmed by talk of a possible break-up of Nigeria, Ankrah quickly interjected and told his guests that “There is no question of secession when you come here [Ghana]”. Although the FMG delegation was keen to mollify and make concessions to Ojukwu, Lt-Colonel Katsina was hostile and blunt than his other colleagues. He declared matter of factly to Ojukwu: “You command the east, if you want to come into Nigeria, come into Nigeria and that is that”.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL DEBATE

Back then as now, each region of Nigeria was petrified of domination by other regions. No region of the federation was keen to adopt a course which would concentrate too much power at the hands of Nigeria’s central government. Even Gowon acknowledged this (and unwittingly played into Ojukwu’s hands) by admitting that he would “I would do away with any decree that certainly tended to go towards too much centralisation”. Ojukwu pounced on the central powers theme and remarked that “Centralisation is a word that stinks in Nigeria today. For that 10,000 people have been killed” (this figure was later revised up to 30,000, and then 50,000). The clash, and ill defined relationship between Nigeria’s central and regional governments has been the greatest source of political bloodletting in the country’s history. It led indirectly to the gruesome “religious” clashes that resulted in the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians over the introduction of Sharia law in some northern states in 2000. It led to the civil war in which over a million civilians died. It led to the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa after he agitated for greater self determination for his Ogoni people.

Using his “skilful histrionics and superior intellectual adroitness”, Ojukwu managed to get the other Colonels to understand, and share his reasoning: that in order to keep Nigeria together as one nation, its constituent regions first had to move a little further apart from each other. Ojukwu used a metaphor to explain his reasoning: “It is better that we move slightly apart and survive, it is much worse that we move closer and perish in the collision.”

This may have been a paradox, but the Colonels accepted the logic of Ojukwu’s argument. The problem then (as it still is in Nigeria today) is that Nigeria is so large, diverse and unwieldy that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to find a leader who can elicit popularity and a following throughout, or most of the country. Amazingly Gowon accepted Ojukwu’s thesis without really understanding the constitutional implications of what he was agreeing to.

Gowon was effectively sanctioning measures which would paralyse his own powers. Lt-Colonel Katsina and Colonel Adebayo also agreed and were attracted to the concept of regional autonomy. Adebayo agreed so enthusiastically that he advocated a “repeal [of] those Decrees that were passed after 15th January, 1966 but I think we should revert to what the country was as at 14th January, 1966, that is regional autonomy”.

Ojukwu envisaged a titular Head of State that would act only with the concurrence of the various regional governments: “what I envisage that whoever is at the top is a constitutional chap – constitutional within the context of the military government. That is, he is a titular head, but he would only act where, say when we have met and taken a decision”.

Having got what he wanted Ojukwu was not content with the agreement to be an oral one (even though it had been taped). He insisted that “we must write it down in our decisions quite categorically that the legislative and executive authority of the Federal Military Government shall be vested in the Supreme Military Council because previously it had been vested in the Supreme Commander”.

The reason for this nuanced request from Ojukwu is that Gowon was now the Supreme Commander. By vesting official authority in the SMC (of which Ojukwu was a member) rather than the Supreme Commander Gowon, Ojukwu could ensure that no official decisions could be taken without his consent. To signify the limited powers that would be exercised by the Head of State envisaged, Ojukwu proposed that the diluted phrase “Commander-in-Chief” should be used to address the Head of State as opposed to “Supreme Commander” (a phrase signifying immense power). The title “Commander-in-Chief” has been employed by every Nigerian Head of State subsequent to Aburi.

While the other delegates arrived at Aburi with a simple, but unformulated idea that somehow, Nigeria must stay together, “Ojukwu was the only participant who knew what he wanted, and he secured the signatures of the SMC to documents which would have had the effect of turning Nigeria into little more than a customs union”.

Ojukwu managed to get virtually everything he wanted, and was so pleased by his success that he even declared that he would serve under Gowon if he (Gowon) kept to the agreements reached. At that point, Gowon arose from his table position and embraced Ojukwu.

The fulcrum of the agreement at Aburi was that each region would be responsible for its own affairs, and that the FMG would be responsible for matters that affected the entire country: a simple enough concept. Afterwards the officers toasted their reconciliation and agreement with champagne.

The federal delegation’s jubilation was such that on his plane flight home, Ojukwu asked one of his secretaries whether the federal delegation had fully understood the implications of what had been agreed.

Hindsight tells us that no one at Aburi (other than Ojukwu) really understood the constitutional implications of what had been agreed. Ojukwu was obviously delighted with this – hence why he was in such a hurry to implement the decisions taken, and why the Federal Government had to renege on them.

Some have argued that Ojukwu took the SMC for a ride by using his superior intelligence to trap the SMC officers into an agreement they did not understand. Ojukwu was engaged in a constitutional debate by himself against five military officers, and two police officers, yet still got his way. He can hardly be faulted for outwitting opponents that outnumbered him by seven to one. Questions might be asked of the other SMC members of greater numerical strength who allowed Ojukwu to extract such substantial concessions from them.

A CONSTITUTION IN WAITING

By failing to implement the Aburi decisions, Nigeria missed a golden opportunity to find a constitutional arrangement acceptable to all of its constituent parts. Had even half of the Aburi accords being ratified, Nigeria may have saved itself a substantial amount of the subsequent bloodshed that ensued over the next four decades.

It is a sad commentary on the lack of progress that Nigeria has made since Aburi that the issues discussed then (over 40 years ago years ago) are still being argued over today. Back in 1967, the Aburi decisions were not implemented for one primary reason: oil.

Nigeria’s greedy power brokers did not want a loose constitutional arrangement that would deprive them of the vast revenues which Nigeria earns from its crude oil exports. Hence Nigeria is glued together under a powerful central government of a type more suitable to a country with contiguous ethnicity.

Nigeria is quite simply too large, too diverse, and too fractious a country to have an all powerful central government of the type it has today. Across Nigeria, there are groups agitating for greater devolvement of federal power to the regions. Although the mantra of these groups is “restructuring” of the Nigerian federation – what they really intend is what Ojukwu wanted to achieve at the Aburi conference in 1967: a constitutional arrangement that would devolve so much power to the regions that the entity known as Nigeria would exist in name only.

Rather than engaging in another constitutional drafting/conference exercise at which will waste more taxpayers’ money, and serve as a means for corrupt “big men” to get even richer, Nigeria would do well to dip into its archives and review the transcript of the debate at Aburi which is gathering dust in the national archives.

The debate transcript is sufficiently detailed to serve as a constitution in waiting. To learn from the debates and mistakes of the past may ensure a better future for Nigeria. What Nigeria needs is a “constitutional chap” of the type envisaged by Ojukwu back at Aburi. As Ojukwu said “It is better that we move slightly apart and survive, it is much worse that we move closer and perish in the collision.”