Nigeria Faces Import Crisis As Reserves Hit 13-Month Low

• Reserves fall behind South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, Libya

• Reserves fall behind South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, Libya

• ‘Contract-crude swap robbing economy of rising crude gains’

• Low confidence worsening investment outlook

Nigeria’s economy could be leaning against the wind as the country’s external reserves fell to a 13-month low last week, tumbling quickly to $30 billion, the level it was between 2015 and 2017.

Last Thursday, the figure slid to $33.79 billion, as it dropped by $30 million. This represented a 0.09% decline compared to $33.824 billion recorded on Wednesday, June 16. A total of $1.58 billion has been lost in reserves year-to-date, while month-to-date loss stands at $405.33 million, hardly reflecting the marginal gains in rising oil prices in recent months.

The reserves fell by $222.3 million between May 31 and June 10 to $34.0 billion, according to figures published by the Central Bank of Nigeria. The last time it fell below that mark was between June and July of 2017.

The country’s forex reserves continues to trend downwards despite the positive rally recorded in the global crude oil market, with Brent crude currently trading at $73.5 per barrel. It has sustained a steady troubling decline in the past two months after a short-lived upswing that took it to $35 billion.

The foreign reserves lost $120.18 million last Tuesday, the highest single-day loss recorded since February 22, 2021.

This is largely attributed to the decline in crude oil sales, due to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the buying capacity of India, which is one of the world’s largest importers of oil.

However, reports suggest that India’s oil imports are beginning to pick up after months of lessened activities due to the pandemic’s effect on its economy. This also comes as good news to Nigeria as India remains one of the highest importers of Nigeria’s crude oil.

The falling reserves, experts have warned, could leave the country’s embattled economic outlook worse off as the confidence of foreign investors is partly influenced by the size of the reserve. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the figure oscillated between $34 billion to $36 billion and even crossed $36.5 billion occasionally.

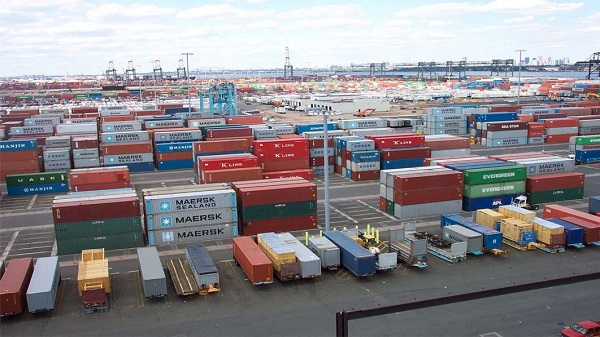

Nigeria’s current reserve is among the poorest of the oil-producing countries. For instance, it is less than 10 per cent of that of Saudi Arabia, world’s leading oil-producing nation, in nominal terms. The real disparity is even wider when the populations and import values of the two countries are compared.

With a population of 35.3 million, Saudi Arabia’s foreign exchange (FX) reserve per capita is over $12,000 while Nigeria’s is about $169, though the imports of the Arab nation far outweigh that of Nigeria with its 2019 yearly imports standing at $144 billion as against Nigeria’s $55 billion.

Other oil-producing countries such as Kuwait, Libya, United Arab Emirate (UAE), Iraq, Iran and Qatar are ahead of Nigeria in both real and nominal reserves.

With respective forex reserves values of $54.1 billion and $40.3 billion respectively, South Africa and Egypt, which are Nigeria’s regional economic rivals, are way ahead in nominal terms. Interestingly, the two countries are not near Nigeria in terms of population and growth in imports, implying that they have given Nigeria a much wider margin in real terms.

On a global scale, Nigeria currently ranks 53rd as the country has dropped further down Morocco and Kazakhstan, whose reserves were previously below Africa’s biggest economy.

Nigeria’s romance with a nose-diving foreign reserves began in August 2008 (at a time the country’s import was less than what it is today) when it hit an all-time high of about almost $64.8 billion.

Data by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) revealed that the country’s import value as of quarter one (Q1) of this year was N6.85 trillion (or $16.7 billion). This suggests that the current reserves can only fund six-month imports, which Bode Ashogbon, an investment consultant and economist, said would put enormous pressure on the monetary authority’s capacity to stabilise the troubled naira.

As experts raised concern over the slide of the external reserve last year, the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Godwin Emefiele, allayed fears, saying the amount could sustain seven-month imports. Notwithstanding the CBN boss’ assurances, analysts have cautioned that unforeseeable market risks, especially as underscored by COVID-19, call for larger external reserves.

Coming at a time Nigeria is battling with her reserves, India’s hit an all-time high of $605 billion earlier in the month, providing an import cover of about 15 months. Yet, the intellectual community of the Asian country is kicking as they feel the amount does not provide a sufficient buffer.

Their argument is understandable as the current reserve of its regional rival, China, can clear import bills of 16 months while Japan has enough to last 22 months. Those of Russia and Switzerland are enough for imports of 20 and 39 months respectively.

As at last September, India’s holding in external currencies could only cover 17 months’ import, a reason the country’s economists are not impressed with the recent growth in the nominal figure.

The CBN, which operates a managed float, periodically supports naira from the reserves, and a lower reserve is expected to affect the value of the currency, which closed on Friday at 412 to the dollar.

Foreign exchange reserves are assets held on reserve by a monetary authority in foreign currencies, quite often used to back liabilities and influence monetary policies. They could be in the form of foreign banknotes, deposits, bonds, treasury bills and other foreign government securities.

Oil revenue constitutes about 60 per cent of Nigeria’s revenue and 90 per cent of Nigeria’s source of foreign exchange earnings, even though it accounts for just nine per cent of the nation’s GDP.

Oil prices have been relatively stable recently, with Brent price selling above $70 per barrel.

External reserves, historically, had been an increasing function of oil prices. But for the first time, the country’s reserve in dollar is falling while the oil market is bullish.

Reacting to the daily slump in external reserves, a former deputy director of the Central Bank, Stan Ukeje, told The Guardian that the situation could have been worse if there were no ban on importation of certain items classified under the prohibition list.

He also explained that the oil prices might not have positive impact on the reserve because not all oil cargos have off-takers. “The rise in price in the spot market for oil does not affect Nigeria’s oil revenue because the country sells on contract. A rise in price in the futures market will materialise only in the future after delivery.

“Also, not all oil cargoes have off-takers. Only international oil companies (IOCs) have steady market access because they are linked with oil refineries, petrochemical plants and strategic storage facilities. Politically connected firms, which are awarded oil lifting contracts by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) have neither vessels nor market access,” he explained.

Ukeje, a financial and investment expert, noted that “some of Nigeria’s oil outputs are pledged to export-import (EXIM) banks and other state lenders in repayment of infrastructure loans,” while the portion so pledged does not bring in foreign exchange inflow “even as the foreign contractors from the lending countries do not bring money into Nigeria.”

The contractors, the ex-CBN banker said, spend the proceeds in their countries of origin, which is part of the reason the bullish crude does not translate to a robust external reserve.

Another investment expert, David Adonri, warned that every import-dependent country, which Nigeria is, needed adequate foreign reserves to meet the rising level of imports, as a key component for economic stability.

Adonri, who has called for full liberalisation of the FX market, said the reserves depletion amid rising oil prices was one of the costs of a managed float FX. “The value of the naira and foreign investors’ confidence in the economy is tied to the level of foreign reserves available. As it depletes, foreign investors’ confidence in the economy is being eroded.

“The main source of forex inflow is earnings from crude oil export held by CBN in foreign reserves supported by diaspora remittances and export proceeds. As the major provider of forex in the economy, CBN can determine the value of the naira and influence imports. With depletion of the foreign reserves, that power is diminished considerably,” Adonri, who is also the Vice-Chairman of Highcap Securities Limited, said.

The declining reserves at a time the oil prices are rising, he said, leaves room for suspicion on the tidiness of the national economic management. With protracted COVID-19 and other economic risks tailspinning into reduced diaspora remittances and foreign capital inflow, economists have continued to balk at the country’s ability to stabilise the reserves.

Ashogbon said the country would need to aggressively address insecurity and increase local production to control reliance on imports and increase export to save the situation. The lowest-hanging fruit, he suggested, was helping the rural dwellers displaced by bandits and terrorists to return to their farms.